Adolescent Health and Development

A Time of Growth and Promise

Adolescence is a time of growth and promise as we experience the environments, relationships, and opportunities that make us who we are. When our fundamental needs for food, shelter, safety, love, and belonging are met and we have opportunities for positive development, adolescence is an intensely meaningful time when we discover how to connect, learn, and contribute.

Tasks of Adolescent Development

There is no hard and fast definition of adolescence, but it can be thought of as beginning with puberty and continuing through brain maturation, roughly ages 10-24.

The domains of development are interwoven and interdependent. How we develop in each domain depends largely on whether our most basic needs are being met and the opportunities and relationships our environments provide.

Physical and sexual development, including puberty, sexual attraction and behavior, sexual and gender identity, and negotiating intimate relationships, is a complex and vital aspect of adolescence. A child's body nearly doubles in size during adolescence as bones lengthen and bones and muscles grow stronger. Puberty intensifies sexual development, including early sexual behaviors such as masturbation. Sexual desires, curiosity, and experimentation are all part of healthy development.

Identity development continues throughout one's lifetime, but adolescence is generally the first time that individuals begin to think about how our identity may affect our lives. The development of a strong and stable sense of self is widely considered to be one of the central tasks of adolescence. Our identities are not simply our own creation: identities grow in response to both internal and external factors. To some extent, each of us chooses an identity, but identities are also formed by forces out of our control. Identity is dynamic and complex, and changes over time.

Emotional development — understanding, expressing, and regulating one's emotions with growing maturity — is key to navigating relationships, functioning effectively in the world, and even recognizing meaning and purpose in life. In adolescence we are often particularly receptive to emotion, and at the same time may be just beginning to understand the nature and effects of intense feeling.

Social development is a major focus in adolescence as we begin to define our place in the world and learn to manage changing relationships, responsibilities, and roles. Parents are no longer seen as all-knowing, and peer relationships increase in importance.

Moral development progresses as we wrestle with personal experiences and greater consciousness of the world. In adolescence we begin to develop our own values and ideals. We develop a more complex, personal, and moral belief system that to some extent will guide our decisions and behavior.

Cognitive and brain development continue throughout the entire period of adolescence, and the changes are dramatic. In early adolescence we think concretely. Most of us in this early period are unable to think abstractly or hypothetically. Our experiences teach us intuitive and analytic thinking and enable us, over time, to make decisions and use good judgment more consistently.

Obstacles to Positive Development

Trauma and Stress

Many children and youth are coping with the effects of past or ongoing trauma. We know that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and complex trauma (exposure to multiple traumatic events) have a cumulative effect, potentially interfering with development [1]. An adolescent who has experienced unstable or exploitative primary relationships, for example, may have issues with health, cognition, emotion regulation, attachment, and behavior. They may struggle with diminished self-worth and operate constantly in survival mode, always feeling unsafe. They may not believe in a better future.

Stress becomes toxic to a child or adolescent's body, mind, and development when the stress response systems are activated over a long period without the buffering presence of protective relationships [2]. In addition to stressors in the home, uncontrollable, toxic stress can come from community stressors such as violence and racism and peer factors such as bullying [3]. Young people may adapt to trauma and toxic stress by either staying in a state of elevated sensitivity — ready to fight or flee — or by disengaging.

Lack of "Normalcy"

When a young person is denied the opportunities that are typical for their peers, their development suffers. While most young people are accorded age-appropriate freedoms to make decisions, have new experiences, and test boundaries, youth who are involved in juvenile justice or foster care systems are likely to have restricted opportunities as well as trauma. The freedom to make friendships, date, learn to drive, take up a hobby, participate in after-school activities, and get a job are all opportunities to regain some control of one's life (a key aspect of overcoming trauma) as well as advance development normally [4].

Adolescent Development: Practical Reminders

Driven by constant change, adolescence is a demanding time for all youth. Though adolescence may be roughly described in terms of stages, youth do not proceed through an orderly, linear progression. Each young person is unique.

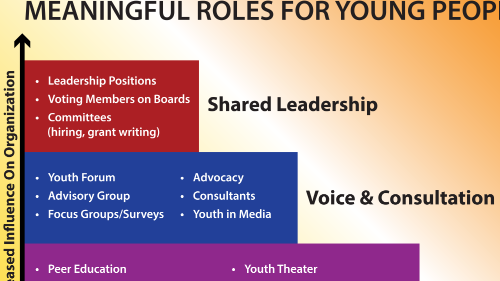

It's always important to keep in mind that development does not happen in a vacuum. In each domain, progress toward adulthood is the result of the push and pull of both environmental and internal factors. Positive outcomes depend not only on a person's own abilities and effort but on available resources. The positive youth development (PYD) approach seeks to surround young people with rich environments, relationships, and experiences that foster growth, personal fulfillment, and contribution.

Key implications for practice include:

- When basic needs for food, shelter, and safety — as well as love and a sense of belonging — are not met, healthy development is even more challenging. Community collaboration is important to ensure that all young people have their basic needs met.

- Bias, trauma, and toxic stress are all too common. Young people need and deserve inclusive, trauma-informed environments and programs.

- All youth need opportunities and supports to build on their strengths and achieve their potential. Organizations and programs can be structured to provide meaningful opportunities.

- Information and awareness are not enough to curb dangerous behavior, perhaps because reward-seeking is dominant in adolescence. Youth programs can help adolescents build on their capacity for good judgment by providing safe opportunities for trial and error.

- Youth need opportunities to take risks in healthy ways because risk taking is wired into the adolescent brain. Youth programs can provide these opportunities for healthy risk and reward.

- Don't take the drama personally! Adolescents may react in unexpected ways. It may help to remember that at this age, the emotional brain is in charge and feelings are intense.

- Social and emotional skills can be taught. Programs that specialize in social and emotional learning can support many of the developmental tasks of adolescence.

- Youth must have strong, positive relationships to develop in healthy ways. Youth programs can offer these developmental relationships.

Resources

The Core Science of Adolescent Development

This overview places current scientific understanding of adolescent development in a narrative form to more accurately tell the story of adolescence. UCLA Center for the Developing Adolescent.

Turnaround for Children Toolbox: Science Foundations

This brief summarizes key points of the science of learning and development, calling out racist/sexist/heteronormative/ableist assumptions and presenting complex ideas in a clear and useful way. Turnaround for Children.

The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth

This report examines the neurobiological and socio-behavioral science of adolescent development and outlines how this knowledge can be applied to promote adolescent well-being and rectify structural barriers and inequalities in opportunity. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Science of Learning: What Educators Need to Know About Adolescent Development

This report summarizes the key developmental changes that adolescents experience in their bodies, brains, relationships, identities, and experiences and explains how those changes impact student learning. Alliance for Excellent Education.

The Intersection of Adolescent Development and Anti-Black Racism

This report summarizes research on how racism and related inequities impact key developmental milestones of adolescence and offers recommendations to support Black youth within key social contexts of the middle and high school years. National Scientific Council on Adolescence and UCLA Center for the Developing Adolescent.

Stages of Adolescent Development (chart)

This easy-to-use tool summarizes stages of adolescence for early, middle, and late adolescent development periods. It makes a great handout for professionals and parents! ACT for Youth.

References

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Effects [Complex Trauma].

- Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University. Toxic Stress.

- Joos, C. M., McDonald, A., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2019). Extending the Toxic Stress Model into Adolescence: Profiles of Cortisol Reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 107, 46-58.

- Simmons-Horton, S. Y. (2017). Providing age-appropriate activities for youth in foster care: Policy implementation process in three states. Children and Youth Services Review, 82, 383-391.